Andrew Hussie also reflects on the comic's legacy, having first launched it a decade ago

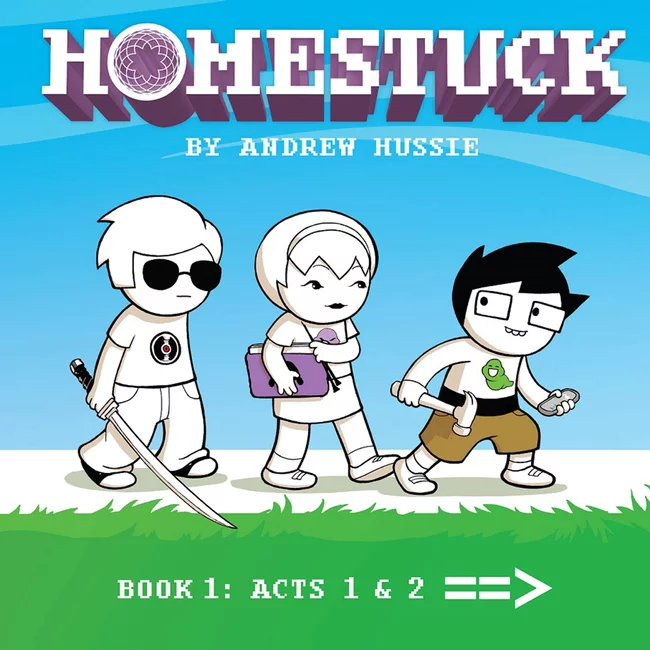

For fans of Homestuck, an exciting opportunity to relive the beloved web comic has finally come to fruition.

Partnering with VIZ Media, creator and artist Andrew Hussie has reformatted Homestuck into a series of hardcover books, featuring the original art and story line as well as new commentary. The first book went on sale earlier this month, and more are scheduled to roll out.

Hussie describes Homestuck, simply, as “Kids play a game, and things go wrong.” But of course, in the thousands of pages and hundreds of thousands of words, Hussie unfurled an entire universe which millions of readers came to know and love. Its complex plot was constructed out of a combination of images, GIFs, and instant message logs, as well as various other animations made with Adobe Flash. And it first launched nearly a decade ago, in April of 2009.

The comic’s popularity has endured, leading to this special new edition. To preview it, Hussie answered some questions for EW about the reformatting process, what fans can gain from delving back into the world, and Homestuck‘s legacy. Read on below, and buy the first book here.

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY: What made you decide to make Homestuck into a hardcover? How did the project come about?

ANDREW HUSSIE: The project came about when I got together with VIZ Media, and we decided to do some things with Homestuck.

We had a lot of cool ideas. Well, I had a lot of cool ideas. And since

they’re like, professionals, they had to say, “You know what Andrew? A Homestuck

theme park sounds great. We’ll get right on that, designing roller

coasters and stuff. We’ll put our top guys on it. But you know, that

could take a long time, since building roller coasters is expensive and

complicated.” I start nodding sagely, like, yeah, of course that’s gonna

take some time. Maybe five or 10 years before they even break ground,

with all the red tape, I can only imagine. So they say, “How about some

books? Let’s just try to hit a few singles first here. We can just print

it out, and sell tangible copies to the fans. People like books,

Andrew. It’s a business model you may have noticed we have some

experience with.” “Oh, yeah, I totally get that,” I said. “It’s a good

idea. We can put a pin in the theme park for now.” I mean, I’m

paraphrasing. There was a lot more to this conversation.

Given that Homestuck was such an internet-based phenomenon, were you hesitant at all?

I think if you’ve read any significant portion of Homestuck,

you would probably find it hard to imagine I would hesitate before

doing just about anything. Besides, there’d be no reason to hesitate

anyway, because books are great. Remember books? The internet is what

sucks. If we could shut it all down, and turn it all back into books

somehow, I’d be fine with that. In fact, why don’t we say what I’m doing

here is leading by example. I showed everybody what you can do with the

internet to tell stories. Now I’m taking one for the team, and saying,

let’s wrestle this horse back in the barn, and call the internet what it

really was, which is one huge mistake.

Talk to me

about your running commentary in the book regarding this adaptation, and

what you wanted to communicate to new and old readers alike with it.

I tend to assume people reading the

books are mostly just the same people who’ve already read it on the

site. In which case, I feel some obligation to put more stuff in there

in addition to the stuff they already read. I’ve described this to

others as a value-add, as if it has some economically-grounded principle

behind it. But really, it just feels like the polite thing to do.

In this reformatting, what were some of your greatest challenges? Was the process easier or harder than you expected?

There’s probably a really interesting

answer to this question that is very illuminating for everyone about

the creative process. But I wasn’t the one who did the reformatting.

Which is good, because it sounds really hard. If I were the one who had

to do it, it probably just wouldn’t have gotten done.

What can those who love Homestuck gain from revisiting the story in this way?

They gain a pretty good excuse to

revisit it at all. It’s good for fans to have an excuse to do that,

because the whole thing is very good. It’s densely packed with funny

jokes, cool ideas, and good characters. It’s drawn pretty badly. But the

panels are shrunken down in the book, so you can’t see how bad they are

quite as easily. Pretty smart, huh? But sometimes the art is good, when

I felt like making it good. Also, there’s author commentary you don’t

get on the site, containing even more jokes. I also explain everything?

All the secrets. Finally, you can stop agonizing over such things as,

why did John have a mental breakdown when he discovers the fruit snack

“Gushers” were manufactured by the Betty Crocker baked goods empire?

For new readers coming into this, how would you describe Homestuck?

Kids play a game, and things go wrong. Beyond that, it’s all pretty straightforward.

It’s been around a decade since Homestuck first captured internet readers. With this new chapter, how are you reflecting on its legacy?

I would reflect on its legacy by

wondering what a legacy really is. I think there are short-term

legacies, which tend to be simple. A lot of people read something, then a

few years go by, and a lot of those people remember reading it and

still think fondly of it. Maybe it meant something to them, shaped their

lives in some way. Maybe they see some books coming out, and decide to

read it again. Or try to get some other people to read it. The word

legacy seems a bit grandiose to use in reference to the situation I’m

describing. The situation being: people liked a thing, and they keep

liking it, as time goes on. This is the kind of legacy that’s more

valuable to me.

A long-term legacy is different. I’m not sure what to think about that subject. That starts getting at the issue of whether something was “important.” Or pushed boundaries, or shook things up, whatever it is that defines importance in a creative sense. Sometimes people send interviews to me and ask about the comparison between Homestuck and Ulysses. My guess is, this is because when an interviewer Googles Homestuck in preparation for the interview, they see this video a guy made in 2012 about that comparison jump to the top of the search. And they understandably think, oh man, this is dynamite. GOTTA ask about this. I don’t have much to say on the substance of that comparison, but I understand why people are attracted to such comparisons. We want to contextualize works that we vaguely sense have qualities related to “importance,” by using certain creative landmarks in history that are also seen as important. Things that got to be important, because a lot of people think and say that, and there’s a long tradition of a lot of people thinking and saying that.

Works that are historically important then gather an aura of reverence around them, which makes comparing them to contemporary things seem overly flattering to new works, or maybe heretical to some. But I’m more inclined to think, sounds about right. Joyce was probably just a joker of his time, flying off the handle with his really intense literary mashup ideas. I think all artists in history who we regard as doing important work were probably just as full of shit as we all are today. Lives checkered with doubts, contradictions, embarrassments, ridiculous indulgences, but through dedication and artifice leave behind works that promote illusions of people in total control, and endowed with endless depth. Like building a hall of mirrors, letting people marvel at reflections of themselves and how far back it all seems to go, then sitting back and taking credit for the very concept of reflection itself, as well as infinity.

But I also think what emerges as important tends to be a product of how much stuff there is to pick from. The further back you go, the slimmer the pickins get. A hundred years ago, there were artists and authors, as opposed to “content creators”. What would we think if the creative world a century ago was comprised of millions of content creators? Would even trying to sift through it to make judgments on relevance cause us to despair? Would the literati be saying things like, “Don’t even get me started on Joyce’s Instagram account.” What’s it going to be like a hundred years from now? Will they say, “Yes, there were several hundred million people with YouTube accounts. But there was this one guy named Pewdie Pie who was absolutely crushing it out there. He was CRUSHING IT!” Will his Wikipedia page say something like, “’Pewdie is considered to be one of the most important pioneers of modernist vlogging and has been called ‘a demonstration and summation of the entire movement.’ [2] According to Declan Kiberd, ‘Before Pewdie, no vlogger of Let’s Plays had so foregrounded the process of thinking.’ [3]”

I guess what I’m saying is, I have this nagging sense that we may be in danger of overvaluing the concepts of artistic importance and legacy in the creative atmosphere that has resulted from the internet. History may, in fact, be laughing at us. Maybe a creator’s job today isn’t to make important things or leave a legacy, but to make sure people in the future are laughing for the right reasons.